Aidan Hagerty

Fungi - the future of the food industry? From locally grown shiitake mushrooms to wild chicken of the woods and giant puffballs, St. Lawrence University student Aidan takes us on a journey of delicious proportions. Aidan begins by introducing us to local mushroom producer Bob Wagner, and giving the listener just the right information if you’re interested in growing your own mushrooms. From there we venture into the forest to harvest wild mushrooms and turn them into quesadillas, pizza, and more. This episode of our Forest Ecology series is sure to make you hungry for some wild delicacies!

Aidan (00:23):

Hi everyone, and welcome back to another episode of Naturally Speaking. My name is Aidan Hagerty, and I'm a student at St. Lawrence University. Today we'll be talking about bizarre and vibrant birds that grow from trees, investment opportunities in your backyard, and I might try and convince you to try out a new diet. I hope to tie together those ideas and maybe make a bit more sense as I share a few stories from this semester and some of what I've learned about the world of fungi. We'll cover some basic questions about what exactly fungi are, talk about the ways that we can coexist and foster beneficiary relationships on our lands, and ask some bigger questions about meeting food, security needs and changing ecosystems and economies.

Aidan (01:12):

We'll start out with a story from the North Country. In the spring and summer months in St. Lawrence County, Bob Wagner, a self-described nomadic and local farmer of sorts, spend his days sourcing logs from primarily red oaks, the occasional hophorn beam, and maybe a couple maple trees. From these logs begins a process of give or take a year. In an odd sort of ritual these logs are drilled with holes and plugged with a parasitic network of tendrils that begin to immediately devour the woody flesh of the log. These tendrils twist and writhe their way through the tender structures, guided by a never ceasing appetite and unique ability to decompose wood. Under the guidance of St. Lawrence Biology professor and mycologist Karl McKnight we are able to witness the fruits of this mystical ritual and meet Mr. Wagner at his local growing operation. A few days before we arrived, a few of the harvested logs ready for their moment were cold shocked in the river, jolting the web tendrils inside of the log and telling them it was time to erupt.

Aidan (02:22):

On each log in the night's leading up to our arrival. Countless shiitake mushrooms had burst through the decaying bark layer and colonized every bare inch of growing space, their bodies a rubbery manifestation of tree flesh. We pulled them off in a line of six by the handful for about 10 minutes, barely scraping the yield from a handful of three to four foot sections of log. Bob said these mushrooms play a key role in his diet. And by the looks of our harvest, the mushrooms seemed enough to meet the nutritional needs of an entire family for weeks at least. In this instance, these mushrooms were headed both for the local market for sale, several pounds were being pawned off in good exchanges with other food producing community members, and a few pounds were gifted to our mycology class for sampling. A remarkable haul given the cumulative time and effort put into this simple agricultural practice. I use the word simple, noting that fungi have been eating up wood and spitting out mushrooms for hundreds and millions of years. But the systematic harvesting of this food supply is relatively unpracticed in Western cultures, but that shouldn't deter you.

Aidan (03:34):

With pre-ordered packs of tree plug spawns, anyone can generate pounds of nutrient dense superfoods. There are guides on YouTube that will help provide some context to this, but by starting a cycle of growing each spring, after one year of lag time for growth, a continuous stream of food can grow from log sections in your backyard. Sure, you're not exactly plucking ready to eat steak or chicken breast off the branches, but Lentinula edodes, the scientific name for shiitake, have been eaten by cultures and generations in Asia for thousands of years. They're prized for their flavor and edibility and are sold in markets as well as directly to restaurants at high rates. There's a really good chance you can turn around enough money to pay property tax, create a food supply, and trade for fresh produce all within a given season with a similar setup to Mr. Wagner's. No matter the scale of the operation, these procedures are a tried and tested method for growing mushrooms and the process can be replicated with various species.

Aidan (04:37):

The mystical ritual I talked about earlier is not as mystical as I painted it out to be. In practice, the process is pretty simple. Given a sizable plot of land, the canopy regeneration provides more than enough growth each year to make up for the sacrifice of harvesting a few branches off standing trees. On a smaller plot, other sourcing options may be more efficient - neighbors cutting for personal firewood, development space, hazards to wires, et cetera, can create several options for sourcing wood locally. Pre-order plug spawns, as discussed earlier - they like to eat different types of wood, so you have to check and make sure the substrate you're using is compatible with the species about to grow. Bob Wagner spends the other months of the year in Kenya. Despite his nature and lifestyle, the Upstate of New York calls him back every year to do this work part-time and play a niche, but important part of the economy of food and agriculture of St. Lawrence county in the winter, the mycelium packed logs lay waiting for his arrival.

Aidan (05:42):

Since we're pretty far into this, I'm gonna take some time to quickly break down some scientific lingo so that it's easier to understand the role that fungi play in the forest. Fungi are a kingdom of life with thousands, if not millions of species represented. They're responsible for recycling cellulose, chiton, and lignin from woody plant debris and organic matter. And so intertwined with our existence it is impossible to live without them. They created the conditions that allow our forests to grow and thrive as they do today, by allowing the forest environment to be recycled and nutrients regenerated. Despite the broad role of these creatures, we've been focused on one example of a saprobic, which means wood, eating species. Each unique species has a role or niche in the forest, which tells us something else about cooperation and living among complex, interdependent systems,

Aidan (06:40):

Saprobic fungi reproduce by creating mushrooms. The creation of mushrooms takes place within the substrate that they're growing on. In the case of these saprobic decomposers, the substrate is the wood and the fungus body inside is called mycelium. The mycelium are the mysterious tendrils I was talking about earlier. Worming around the lignin and woody tissue, they leach nutrients from the tissue, rendering cells recycled and nutrients usable. With a mind of its own the mycelium continues to harvest until it is ready to spread spores and send a mushroom into the world. Not all the species of mushrooms can be coaxed to grow as easily as Lentinula edodes or shiitake. Due to the complexity of reproductive structures and the specificity for certain environmental conditions, some of the most delectable species can only be properly harvested from the forest.

Aidan (07:38):

Speaking of delectable treats, I have another story to share. In late September, I was running around trails on St. Lawrence campus. When I happened to look up into the canopy of a large oak tree in the Kip forest. In a fissure about 25 feet off the ground, I was blown away to see a beautiful yellow and orange bird protruding from the torn agape bark. I was surprised that no other runners had found this tasty pot of gold before realizing I was gonna need to enlist some help to get the chicken off that tree. I ran my way back home and returned a few minutes later with Ben. Soon after we had poked and prodded a sizable chunk off the tree. And an hour later from that, we were devouring the beast back home. Now you're probably pretty sure that chickens don't grow on trees and disappointingly or approvingly understand I'm talking about mushrooms, given the context of the podcast. However, Laetiporous sulphureus, or chicken of the woods, when cooked right, can fool the finest chicken connoisseurs.

Aidan (08:37):

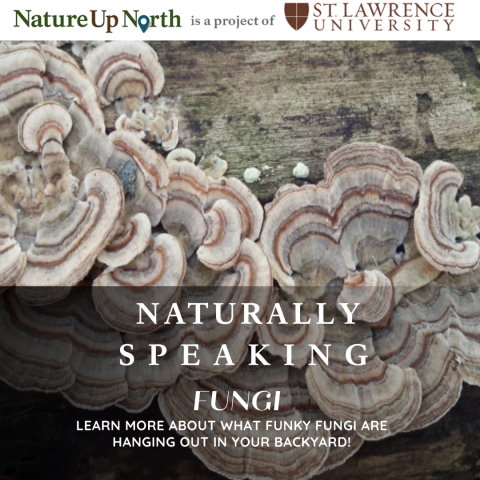

Like it's distant relative the oyster mushroom, it is saprobic or wood eating. Unlike the oyster mushroom, chicken of the woods is a polypore. This means it does not have gills, and instead forms a small surface of pores on the underside that act in the same fashion - to spread spores into the local environment. It makes for a fine feast if you cook it right. With a stick of butter, some odd spices from our rapidly deteriorating college kitchen, and a cast iron pan, we cook the mushroom meat to golden brown with assorted peppers and served quesadilla after quesadilla to my housemates. The unfortunate news is that chicken of the woods is a picky species to grow with pre-seeded plugs and mycelium spawn. It is usually outcompeted by other fungi if you try inoculating your own logs, but when someone figures out a way just grow them locally, I will definitely be giving it a try.

Aidan (09:33):

If you've never cared for mushrooms, I'm willing to bet that anyone would enjoy chicken of the woods for its delicious flavor and texture. In the few hours outside of class that my friends and I explored the woods, we accumulated pounds of the orange and yellow striped fowl. I attached some pictures for reference for identification, and to prove that you can make tasty quesadillas. The pounds you collect are slabs of protein dense, low carb, and low calorie foods that you can theoretically cook, freeze and enjoy later, give away or sell, and then keep some for decoration or something. We only took a fraction of the specimens that we found in the case of the story above. We took maybe a 10th of the total flesh of the mushroom. However, this was for the combined reason that we couldn't really poke down anymore with our 25 foot long stick, and just taking clear shelves of chicken of the woods is recommended for eating. While the forest is free range for fungi hunting, there are some ethics of mushroom picking that you should adhere to which I'll get into now.

Aidan (10:39):

To start off when you pick mushrooms, you're not killing them. In fact, you're mostly helping. The mere act of picking up these sensitive beings is sending millions of microscopic spores into the air. Completing the work in the mushroom body, assuming the spores are ready to move. Now, don't go making a mess of the forest but yes, it is definitely okay to pick up and take home some free food if you see it. The main takeaway from this ethics lesson is the following: <alarm noise>

Aidan (11:10):

Don't eat it unless you're 10000% sure that it is edible. There are ways to make sure of this, most importantly is buying a guide for identification. I would recommend the Peterson field guide for fungi, but there are also resources online where you can ask or send an email to mushroomID@whitemountainmushrooms.com. They should reply with a identification. Generally, the members of the species and the list I provide in this podcast don't have many lookalikes and I'll provide some images as well that will be linked to this. Between that and looking online should be enough to get you started. I use pictures for reference from mushroomexpert.com because I know it is reliable and a safe reference, given you already have some idea about the species you're looking for. Check out the links attached.

Aidan (12:09):

My introduction to myology textbook quotes, Bryce Kendrick in the fifth kingdom. "If we use a 10,000 square meter plot, or a hectare of land to produce beef, the yield of protein is about 80 kilograms for that 10,000 square meters or hectare. However, if we grow mushrooms, the protein yield 80,000 kilograms for that one hectare." Companies and industrial growing operations understand this statistic, but this business is just emerging. The model makes sense to follow - high yields of organic waste can be recycled in the growing process to create food for your table. From sawdust comes your dinner. Just across from us in Ontario, there is Carleton Mushroom Farms LLC, who've made a business out of the manufacturing of mushrooms. They sell by the order and have mastered the business model of industrial manufacturing. There is another company called Ecovative in Albany that uses the growth of mycelium to meet all kinds of packaging and insulation needs. Worth checking out for investments? I'm no economics major, but I'd argue that the market's worth selling your crypto currencies for. I also included the links to these websites attached to this episode.

Aidan (13:31):

You may be asking what about my backyard? Who cares about all that? I think you should care because the real power of the mushroom movement lives in the backgrounds of homeowners. St. Lawrence County is gifted in its geographic position. Gets a lot of rain, has rich soil that relies on fungi to recycle and renew the canopy. However, a lot of the North Country has low access to fresh produce, or is considered a food desert. The fungi here are documented and readily available on public land, and with four and a half millions of acres of it at the hands of publicly conserved lands, I'm here to tell you that the odds of finding dinner are pretty good if you know what you're looking for. There large swathes of forest in the Adirondack Park, and more locally at Glenmeal, Donnerville, South Hammond, and Peavine Swamp state forest and preserves.

Aidan (14:25):

Besides a few outliers like these companies that work with mushrooms, the market remains untapped in the North Country. In the grassroots movements at the work of individuals can meet a lot of demand that otherwise industrial growers would cover. Perhaps it's worth buying $15 worth of plugs and seeding some logs, or spending a few hours gathering and storing edible species next summer and fall. Foraging efforts, even in the context of spending an hour outside walking a local path, or a way that you, or maybe your kids if you have them can gain an appreciation for nature and literally save you money at the same time. And they said money didn't grow on trees. Rich sources of antioxidants, proteins, and other nutrients are quite literally at your fingertips if you go looking.

Aidan (15:13):

So now we're gonna need a list so that you can have an idea of what to go looking for exactly. Like I said earlier, buying an identification guide would be the most helpful and safest idea, but the few examples I'm going to offer are unique enough that identification should be rather straightforward. I again, would like to plug the Peterson field guide, because it was written in part by St. Lawrence professor, Karl McKnight. It is available to order or perhaps can be checked out of the local bookstore. The radial yellow and orange lined chicken of the woods, which has several great images on the internet to reference and some attached from my own collection. The are a few other extremely common and easily distinguishable delicacies you should be aware of. One of these are smooth puff balls, or Lycoperdon molle is the scientific name. These are the white spherical mushrooms often growing in groups on the forest floor. They're only edible when the interior is completely white and squishy, turning poisonous black, and powdery when inedible. It is easy to tell if the interior is safe, just cut the mushroom in half. When preparing these, cut them into pepperoni like slices and throw them into a pan with butter -mushrooms like butter, it is usually the base of which I cook them in.

Aidan (16:30):

You can find them pretty much anywhere in Northeastern forest and throughout summer and fall. A hundred percent success rates guaranteed. I bet you could find them anytime you walk the forest in those seasons. There are also giant puff balls, which I'm sure you could identify now if you came face to face with one. Picture a giant white ball and you've got a pretty good idea of what to look for. Due to their size it is easy to cut the ball into slices, the same way you would a smooth puffball and make pizza crust with circular slices. Just add some olive oil and bake the mushroom at around 400 degrees for 10 minutes, add your sauce and cheese and put the pie back in for maybe five to seven more. Just feel it out. You can also try for giant puffball steak, if that's more your thing.

Aidan (17:16):

Just as with the quesadillas and chicken of the woods, I have pictures included of the result of my own pizza making for reference. I think I made the crust too thick, so keep it to half an inch or so thickness when you try yourself. Honey mushrooms are yet another prize edible mushroom that are widespread in Northeastern forests. They're yellowish brown, which is slightly variable on the cap, which rises slightly in the center. The stalk darkens towards the base and has a ring towards the top of the stem. There are pictures online that will give you a better idea of what to look for and pick for eating. If you find some are feeling not too creative, just cut them into small slices and butter 'em up in a pan for some mushroom toast.

Aidan (17:59):

I wanna say good luck out in the forest and good on you for having an open mind and making it through this episode. I hope that you've considered existing symbiotically, some of these fungal creatures, you may have never considered. While we think about emerging issues of food sovereignty, climate change, land use for agriculture and the dietary needs in the North Country, fungi do have many answers. On a more personal level, they're fun to forge and eat - also one hundred percent free. Anyway, thank you for listening to this episode of Naturally Speaking, go get outside and look for mushrooms.